|

| A jumble of pipes and a huge amount of lava - it's the future! |

The model is here on our SketchFab page. This system is discussed in the section on solar thermal turbines on the website. We started talking about the heat storage mass. Right now the hot pipes from the mirrors dive straight into the ground and the deep pond of lava created around them simply has to be big enough that even as heat drains from it all through the long night, it is still hot enough to heat the gas that drives the turbines. Powder regolith insulates very well, so that actually isn't as crazy as it may sound. However, it does mean that a lot of the mirrors in the system are simply there to make the heat store big enough to last through the night. Mirrors are simple to make, so why not just make those extra ones instead of making an actual tank to hold a huge amount of lava? Well, the pipes full of molten salt that carry that heat back to the reservoir are not simple to make and will need repair more often, and the longer they are, the less efficient they are. Besides, once you have made the tank, the performance of the whole system goes up, and stays up. Such a tank will last a very long time with little upkeep.

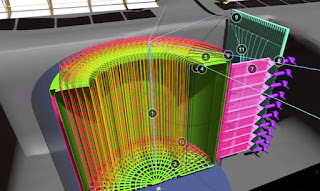

The joy of engineering on the Moon is the low gravity and the hard vacuum, when you can make it work for you. In this case, it works for you like busy bees. The reason powder regolith insulates so well is because even when it is packed hard it is half empty space - truly empty, vacuum, which means no heat conduction or convection. So, since the same material on the Moon can support six times as much mass as it can on Earth, the best way to make a gigantic tank out of local materials, that is capable of containing a vast amount of lava, is to pack powder regolith around the lava in a very thick layer and make sure it doesn't melt. Then the heat that reaches the outer skin of the tank is low enough to make the tank out of poured stone (which is to say, out of molded lava). Heat is actively pumped out of the tank to run the turbines from the bright green layer in the image that forms a sort of inner tank. The system needs to keep that tank near the temperature that is best for the working fluid the turbines use.

(The notes on the SketchFab model talk about that. I have been told some of those notes run off the screen. If that is happening you can make the model full screen by clicking the icon of two arrows in the bottom right corner.)

The model doesn't show all the reflective insulation that goes all over (among other things - it is far from finished). Heat lost by infrared radiation can be reflected back by metal foil. By using two or three layers of it, heat loss can be hugely reduced in a vacuum environment. Aluminum reflects back about 90% of the heat that hits it, silver reflects about 97%. Since it only takes a microscopically thin layer to do the reflecting, we might as well use silver for all the radiant barriers. This ability to control heat loss makes this whole system work a lot better. "Don't try this on Earth" (heh heh heh).

Heat stores are more efficient the larger they are. Heat spreads by diffusion, so the farther it has to diffuse to leave the heat store, the smaller the fraction that leaves. Thus Sigvart is advocating for a Nuclear Lava Lake. His simulation program reports** that a lava store 2 km across would lose only 3 W per m<sup>3</sup> over an entire night, which is pretty sweet. Also, a lava lake is pretty sweet, if you can manage it. We didn't talk about how deep it would be. His program doesn't consider depth at the moment. I have imagined the future colonists asking the robots that built the lake how deep it is, and the robots responding "Who's asking?". There is a small mountain to the south of Lalande that likely has good highlands feedstock for glass production, we could mine that for the glass for the city and then fill in the resulting hole with the lava lake when we are done (or rather, when the robots are done). Sure, let's do that. Oh, and the nuclear part? Sigvart suggested a 'controlled nuclear meltdown' to supplement the lake's output. I have to ask him about the details, he has been busy since then. I suppose basically one lowers a nuclear core into the melt and the flow of lava around it distributes the heat and that basically works. That could be alright i guess, although that lava is useful for other things and it would be nice if it wasn't radioactive so some can be tapped for use in industry. Nuclear Lava Lake Park has a nice ring to it, though.

So now we are trying to rough in some details like what the working fluids should be, sizing of the different pieces, and more turbine design. The turbines shown are really just placeholders right now. I am leaning towards trying to get this power plant model developed, together with a tether complex model, and improvement to the colony habs, and then make those the showpieces for a campaign to go to the next level. That should be enough to take the concept on the road and try to put together the alliances needed to assemble a dedicated team to complete the core of Moonwards. I think that goal is a reasonable one, but that we couldn't go much further without an actual staff.

People have started to appear and take an active role in working on this. It's really pretty cool. It makes me keenly aware of the need to provide them with better tools and work much harder on communication and coordination -but it's very cool. As the virtual colonies themselves reflect, the approach here is to Go Big. The Wiki section of the GitHub repo will start getting its overhaul next week, in which sections devoted to resources for the key models - the solar thermal plant, the tether complex, and the main habs - are created and developed. The repo will hopefully start behaving like a full repo, with issues, projects, and pull requests. It totally deserves to, Moonwards is a great idea. It's just a question of creating the medium in which it can grow.

**Note: If you download the program, compile and run it in a terminal with this command: g++ -o gradient temperatureGradient.cpp && ./gradient

No comments:

Post a Comment